By Hans Detlefsen

Introduction

Although many communities have identified the need for a new hotel or conference center, market demand may not be sufficient to cause the private sector to develop such projects. If developers expect a project’s costs will exceed its investment value, then a “feasibility gap”[1] may prevent the private sector from investing in the project. Public-private partnerships can be an effective means to initiate economic development projects of this nature.

The public sector’s role in a public-private partnership often includes providing some form of financial or tax incentive to close a feasibility gap between a developer’s total project cost and the estimated value of the completed development. The Appraisal Institute[2] provides the following definition of economic feasibility:

An investment’s ability to produce sufficient revenue to pay all [project] expenses and charges and to provide a reasonable return on and recapture of the money invested.

What can public sector officials do to minimize the need for subsidies? How can governments get the biggest bang for their buck?

This article will focus on one key metric to determine which potential developers are likely to require the smallest and largest subsidies. This sometimes-overlooked metric, the “cost of capital” to developers, can be a critical factor in determining the amount of public subsidy a given developer will need for a defined project. A strategy to minimize public subsidies involves seeking the most qualified developer who also has the lowest cost of capital. Although such a strategy may be applicable to many development types, this article pertains specifically to the relevance of determining developers’ costs of capital in the context of developing hotels.

When public sector officials identify hotel development projects as priorities, they typically seek private sector expertise and investment to help develop the project. To initiate the search for a development partner, public officials often rely on a competitive process, such as a Request for Proposals (RFP), to solicit development proposals from private sector developers. Such RFPs typically aim to identify a private-sector stakeholder to develop, own, and operate the proposed property as part of a public-private partnership.

Hotel Example

Let’s consider an example. For the sake of this article, we assume that a community is comparing two potential private-sector development partners as finalists for a desired hotel development. In general, we find that communities can compare development proposals on the following basic criteria, among others:

- Knowledge and experience of developer

- Project cost or quality[3]

- Income potential of project

- Cost of capital (or funding strategy)

In this article, we assume both developer finalists have similar knowledge and experience pertaining to hotel developments. Furthermore, we assume they both agree on the hotel’s construction cost and have plans that indicate identical quality. Finally, we assume both developers forecast similar or identical income potential for the hotel.

The only difference between the two developers is their funding sources, which cause them to have different costs of capital. Hotel funding typically includes both equity and debt components. As different developers have access to different sources of equity and loan financing, the funding aspect of a hotel development can play a crucial role in determining a developer’s total project cost. This article will discuss the importance of identifying the developers’ costs of capital as a selection criterion for public sector decision-makers administering an RFP process of this type.

Measuring the Feasibility Gap

A feasibility gap can be defined as the difference between a project’s cost and its value. How can one determine whether a feasibility gap exists? And how can it be quantified?

To calculate a feasibility gap, hotel appraisers rely on quantifying two numbers for comparison: (1) the total development cost of the project and (2) the anticipated investment value[4] of the project upon completion. If the project’s anticipated investment value is greater than its total development cost, then the project is feasible and would not require public-sector incentives. However, if the total project cost is greater than the investment value, then a feasibility gap exists. The size of the feasibility gap is measured by quantifying the difference between the project’s cost and its value.

Developers or cost estimators can provide detailed estimates of a hotel project’s cost. An experienced hotel appraiser can estimate the proposed hotel’s value upon completion. The comparison of these two numbers allows one to quantify a project’s feasibility gap, if one exists.

There are three basic approaches used by appraisers to estimate value: (1) Income Approach; (2) Sales Comparison Approach; and (3) Cost Approach. The Income Approach is often the most appropriate approach to rely on when evaluating income-producing properties, such as hotels. Within the Income Approach, appraisers may consider several techniques for estimating value, but one of the simplest techniques is known as Direct Capitalization. This technique allows one to estimate a property’s value by dividing its earnings[5] by an appropriate overall capitalization rate. Although the Direct Capitalization technique is not always recommended for valuing complex properties, such as hotels, the technique is useful in illustrating the importance of evaluating developers’ costs of capital. This simple technique can be expressed as the following formula, familiar to most appraisers:

I / R = V

In this formula:

I = income or earnings

R = overall capitalization rate

V = value

This article focuses on the importance of capitalization rates used by potential developers. For the purpose of this article, a capitalization rate can be thought of as the overall “cost of capital”[6] to the developer. Based on the preceding formula, then, one can see the relationship between a developer’s cost of capital (or required financial returns) and the resulting feasibility gap. The higher a developer’s cost of capital is, the lower the developer’s derived investment value will be. In other words, all else being equal, the higher a developer’s cost of capital is, the more subsidies this developer will need.

Comparing Developers

Suppose a local government has issued an RFP for the development of a 500-room, full-service hotel. Then, assume two developers have been selected as finalists, based on their knowledge, experience, and other qualifications, as previously indicated. Assume both have estimated the total development cost for the proposed hotel to be $162,500,000. So, to determine whether a feasibility gap exists, we need to estimate the investment value of the project to each of the two finalists and compare these values to the development cost estimate.

Based on the formula shown earlier, we can estimate the investment value to each developer if we know the hotel’s expected earnings (I) and the developer’s cost of capital (R). For illustration purposes, assume both developers are forecasting similar financial operating projections for the hotel, indicating an EBITDA less replacement reserve of approximately $11,500,000 annually. We can divide this income figure by the cost of capital for each developer to estimate the investment values to these respective developers. We can then compare these values to the estimated development cost to quantify their respective feasibility gaps, or required subsidy levels.

Assume the following descriptions about the two developer finalists:

Developer #1 has an investment partner who is willing to provide equity for this project and requires a 15.0% return on the equity contribution invested. Based on this developer’s current banking relationships, she also has a letter from a bank indicating she can obtain a loan for 70% of the project cost, amortized over 30 years, at an interest rate of 4.5%. The resulting mortgage constant is roundly 6.1%. Therefore, Developer #1’s weighted average cost of capital is about 8.8%.

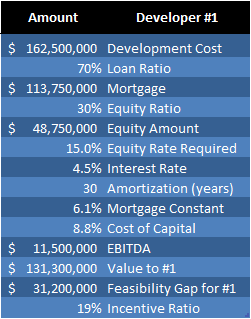

The following figure summarizes this calculation and provides an estimate of Developer #1’s feasibility gap for the project.

Figure 1 – Feasibility Gap for Developer #1

Based on these assumptions, the indicated investment value of the completed hotel is about $131.3 million to Developer #1. This leaves a feasibility gap of approximately $31.2 million. The feasibility gap can be thought of as the required level of public-sector (or other) subsidies needed to allow Developer #1 to attract funding for the hotel project. This incentive requirement represents roughly 19% of the estimated total project cost.

Developer #2 has an investment partner who will provide equity for the same project, but requires an 18% return on the equity investment. The developer’s bank will offer a loan for 65% of the project cost at an interest rate of 5.0%. Note that this developer has access to a loan with a higher interest rate, and a lower loan-to-cost ratio, compared to the other developer. The resulting mortgage constant is approximately 6.4%. Based on these findings, Developer #2’s weighted average cost of capital is about 10.5%.

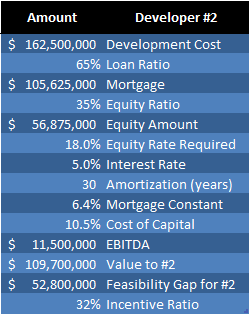

The following table summarizes this calculation and provides an estimate of Developer #2’s feasibility gap for the same project.

Figure 2 – Feasibility Gap for Developer #2

Based on these assumptions, the indicated investment value of the completed hotel is about $109.7 million to Developer #2. This leaves a feasibility gap of approximately $52.8 million. This feasibility gap represents roughly 32% of the estimated total project cost.

Developer #2 has a much larger feasibility gap than Developer #1, even though the two developers proposed an identical development project. The difference is that Developer #1 has access to a significantly lower cost of capital. Therefore, Developer #1 can complete the project for a substantially smaller public-sector subsidy than Developer #2.

This article specifically highlights the importance of comparing parameters that influence the overall cost of capital. In the hotel example, there were two key differences. Firstly, the loan-to-cost ratio and interest rates both affect how much of the total funds required can come in the form of debt, and at what cost. Secondly, the equity yield rate, or the required return on equity for the investors, reveals how expensive it will be for each developer to access the remaining portion of funds from equity capital sources.

Conclusion

The preceding example illustrates how differing capital costs can greatly affect feasibility. In this example, the two equally qualified developers would have very different requirements in terms of public subsidies needed to complete the same project. By evaluating the cost of capital available to potential developers, policy-makers may be able to gain important insights about the potential subsidies that will be required to complete a desired development project.

As illustrated, the cost of capital can make a big difference in terms of whether a hotel project is feasible and to what extent developers may require public subsidies to complete projects. Developers can sometimes have significantly different costs of capital, depending on their funding sources. For this reason, public-sector decision-makers aiming to attract hotel developments to their communities may wish to evaluate these funding sources and any differences in capital costs when comparing developers.

Financing full-service hotels often requires some form of public subsidy. But investigating the financial capacity and funding sources available to potential private-sector development partners can help public-sector participants maximize the return on their public investments. Hotel Appraisers & Advisors[7] provides advisory services to help clients evaluate development deals and public-private financing strategies.

This article is for discussion purposes only and is not intended to be construed as investment advice.

[1] A project’s feasibility gap can be quantified as the amount by which a project’s cost, including indirect costs and a developer’s profit, exceeds the project’s anticipated value upon completion. [2] The Appraisal Institute, The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 4th Edition (Chicago: The Appraisal Institute, 2002), 91-92. [3] Variations of this criterion could include a project’s ability to generate economic impacts, jobs, or fiscal impacts. [4] Appraisers can use market value instead of investment value when estimating market feasibility. But in this article, we focus on investment value to compare two specific developers with differing costs of capital. [5] Earnings Before Interest Taxes Depreciation and Amortization (EBITDA), less a replacement reserve. [6] This cost of capital is typically a blended cost of various forms of debt and equity funding, which have required financial returns (i.e. interest rates and equity yield rate requirements). [7] www.hotelappraisers.com